Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

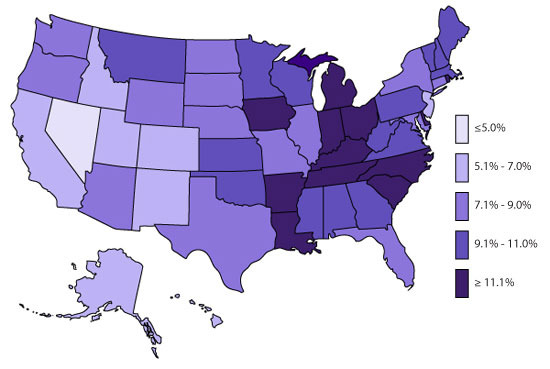

State-based Prevalence Data of ADHD Diagnosis (2011-2012): Children CURRENTLY diagnosed with ADHD

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). State-based prevalence data of ADHD diagnosis (2011-2012): children currently diagnosed with ADHD. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/data.html

Introduction to ADHD

ADHD or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is characterized by the National Institute of Health as "a problem with inattentiveness, over-activity, impulsivity, or a combination." These qualities must be beyond the average range for the student's age group to be diagnosed with ADHD (National Institute of Health, 2011). In 2007, about 9.5% of students in the United States ages 4-17, or about 5.4 million students, were diagnosed with ADHD (Center for Disease Control, 2013). Based on these percentages, about one out of ten students has been diagnosed with ADHD.

ADHD Subtypes

ADHD is often divided into three symptoms or subtypes: inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Parents and teachers frequently do not realize that inattentive students have ADHD because these individuals are often quiet and less likely to act out. These students may sit quietly, seemingly doing their work, but they may not be paying attention to what they are doing. Students who are inattentive may also get along well with other children, unlike students exhibiting hyperactivity and impulsivity, who tend to have social problems. However, students with the inattentive subtype of ADHD are not the only students whose disorders are easily missed. For example, adults may think that students with the hyperactive or impulsive subtypes of ADHD simply have emotional or disciplinary problems (NIMH, 2008).

| Inattention | Hyperactivity | Impulsivity |

|

often does not pay close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, work or other activities

|

often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat

|

often blurts out answers before questions have been completed

|

|

often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activity

|

often leaves seat in classroom or in other situations in which remaining seated is expected

|

often has difficulty awaiting turn

|

|

often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores or duties in the workplace (not due to oppositional behavior or failure to understand instructions)

|

often runs about or climbs excessively in situations in which it is inappropriate (in adolescents or adults, may be limited to subjective feelings of restlessness)

|

often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games)

|

|

often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities

|

often has difficulty playing or engaging in leisure activities quietly

|

|

|

often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort (such as schoolwork or homework)

|

is often "on the go" or often acts as if "driven by a motor"

|

|

|

often loses things necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., toys, school assignments, pencils, books or tools)

|

often talks excessively

|

|

|

often is easily distracted by extraneous stimuli

|

||

|

often is forgetful in daily activities

|

Treating ADHD

The most common treatment for students with ADHD is medication; in 2007, about 66.3% of those diagnosed with ADHD were being treated with medication, such as Ritalin, Adderall, and Dexedrine (Center for Disease Control, 2013).

While the medical community may view ADHD as a disorder with genetic and physiological causes, some researchers and advocates argue that ADHD is a socially-constructed explanation to describe behaviors that do not meet prescribed social norms (Parens & Johnston, 2009). These researchers suggest that while the traits that define ADHD are measurable, they nonetheless lie within the spectrum of healthy human behavior and are not inherently dysfunctional (Timimi & Begum, 2006). Thus, in societies and contexts where passiveness and order are highly valued, those on the active end of the spectrum will be seen as "problems"; and vice versa, where activeness is highly valued, passiveness will be perceived as problematic.

Girls are less likely than boys to be diagnosed with a learning disability and cause problems in school or in their spare time, while being more likely to have the predominantly inattentive subtype of ADHD. This does not mean that there are fewer girls with learning disabilities than boys. In fact, some ADHD researchers and advocates express concern that this underrepresentation increases the likelihood that girls, who go undiagnosed for ADHD, will be at-risk for chronic low self-esteem, underachievement, anxiety, depression, teen pregnancy, and early smoking during middle school and high school (Crawford, 2003).

Accommodations in the Library

In a library, structured, one-size-fits-all teaching and testing methods that require passive behavior may be inappropriate for students with ADHD. This theory of ADHD advocates using interactive learning techniques, activities in the library, organizational and structural methods in instruction, and granting accommodations where necessary to create an accessible library for all students.

References

Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (2013). ADHD, data & statistics. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/data.html

Crawford, N. (2003). ADHD: A women's issue. Monitor on Psychology, 34(2). Retrieved from: http://www.apa.org/monitor/feb03/adhd.aspx

National Institute of Mental Health. (2008). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder/complete-index.shtml

Parens, E. & Johnston, J. (2009). Facts, values, and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): an update on the controversies. Child & Adolescent Psychiatry & Mental Health, 3(1). Retrieved from: http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/1

Timimi, S. & Begum, M. (2006). Critical Voices in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. London: Free Association Books.